Captain’s Inspection – Stand by your Bunks

by David Reid MA FNI

Sunday morning at sea meant a thorough tidy and cleaning of our cabin onboard a British merchant ship. As navigating cadets, we were subjected to a very thorough inspection by the master and senior officers at 11:00. So immediately after breakfast the focus for the morning was on a deep clean of the cabin, typically each ship carried two navigating cadets and we shared a cabin. Two bunks, two desks and two chairs made up the efficient interior and our cabin was sited close to the cabins of the navigating officers.

Preparing for a Sunday inspection required attention to detail, it was not sufficient to just have a clean deck and superficial tidiness. Everything was inspected, drawers and wardrobes would be opened and checked to make sure that our clothes were neat and in order. The master frequently wore white gloves and would run a finger along edges of drawers and wardrobes to check for dust. Cleaning the brass on our porthole was a critical part of preparing for the Sunday inspection, so each Sunday one of us would be assigned to that task, using Brasso we would apply the white cream to the dull brass and then rub the liquid Brasso in with a damp cloth until the dull surface began to reveal the shine below. Once that began to dry, we then used a second linen cloth to buff the surface and make it shine. `however the screw dogs that secure the porthole were more difficult because their surfaces were curved, and the threads had the tendency to trap the Brasso liquid and this diminished the overall look. Cleaning brass is a pleasing task because the result is always a delight, except that you always know that this is short-lived because it will soon dull as it begins to oxidize. It is a never-ending task.

I learned that there is a trick to surviving a Sunday inspection and that is to leave something undone, the reason being that most senior officers feel that it is necessary for them to find some fault with a command to make it better. It would be a rare and inconceivable occurrence for the master to inform you that your cabin was simply perfect. So, the inspection would continue until some issue of fault was revealed, the better that you cleaned and tidied, the longer the inspection would last. To remedy this enigma, it was therefore prudent to leave something undone so that the master could seize upon that and declare the inspection complete. Of course, this required careful planning because you could not leave the same item undone each Sunday, so this required creative thinking to ensure that we engineered the outcome of each Sunday inspection.

On British ships after the Sunday inspection was complete, the senior team comprised of the master, chief officer, chief engineer, and chief steward would retire to the captain’s cabin for a gin and tonic before Sunday lunch, so in the scheme of the Sunday inspection ritual the chronology of events that preceded the gin and tonics needed to be completed such that the G+T time was not impinged on. This of course reflected an era when the consumption of alcohol on board was quite permissible and in fact encouraged as part of social interaction onboard. British shipowners in the 1970’s became concerned about the welfare of their officers and to stimulate social interaction they decided that it would be prudent to fit mini pubs inside the officers messrooms. Shipping companies dispatched knock down bar kits to each of their ships together with all the accessories to create a miniature bar/pub. This also included a special brew of English draught bitter beer that had been formulated to survive shipment with a very long shelf life. When the kit arrived together with a year’s supply of draught beer the installation of the bar and the fitting of the chiller unit to ensure the beer was served at the right temperature became the primary focus of the engineering department with close supervision and final testing by the chief engineer.

During my last years at sea serving on Canadian flag ships we made a few trips beyond the normal routes within the Great Lakes and on the East Coast, on those occasions when we made trans-Atlantic voyages I led the Sunday inspection, although we carried no cadets we did use the opportunity to make a tour of all the accommodation space to make sure that all the common spaces messrooms and bathrooms were in order. This also included a tour of the galley. As we toured the ship any items that needed repair or maintenance were noted so that a proper follow up could be made and subsequently checked at the next inspection.

In my later years while serving as the Supply Chain Director at the second largest steel plant in Europe this process had a more formal protocol and fell under the auspice of Continuous Improvement “CI”. In the steel industry the practice of routine inspections by management was embedded and we were assigned to inspect other departments and this practice included inspections by the group CEO which was significant in a company that employed 50,000 people worldwide.

The key driver for these inspections was always safety based on the principle that behavioral safety could be improved by adapting the Japanese 5S “Kaizen” methodology. In English this translates into 5 steps, Sort – Straighten – Shine – Standardize and Sustain.

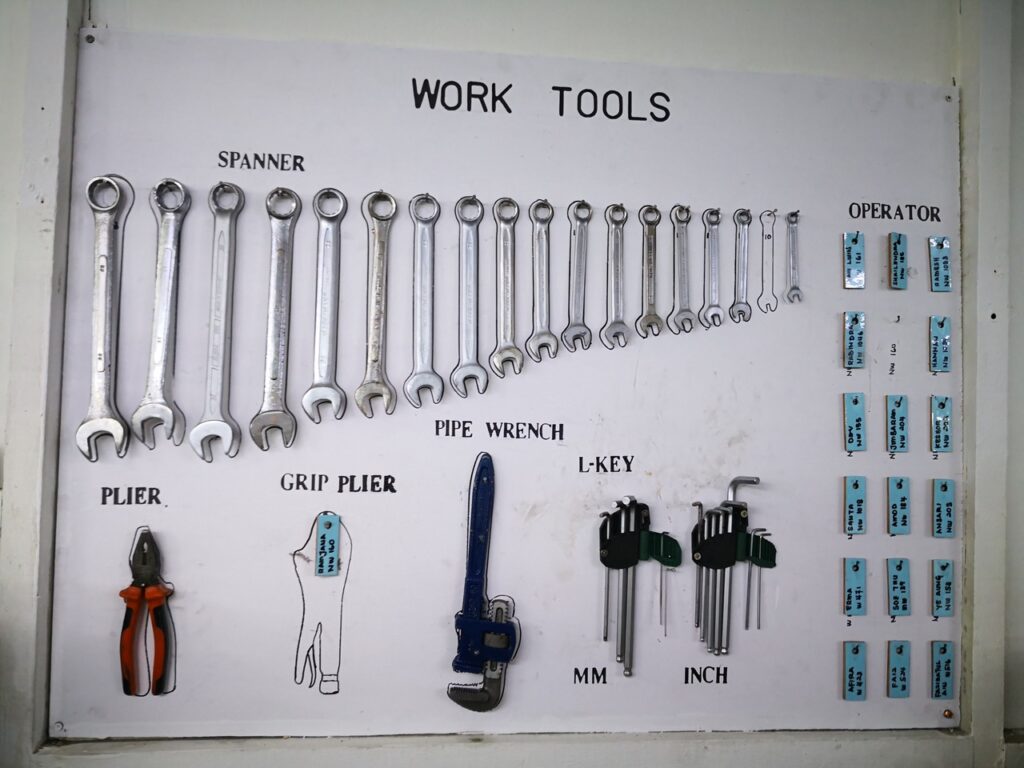

There is now a 6S which adds Safety as the sixth step. Anyone who has worked in or visited a workplace that embodies these 5S or 6S principles will easily see visible evidence of these practices. For example, walkways will be clearly marked, tools will have a designated location where they are stored, work areas are kept clear and tidy. The purpose of the steps is to design the workplace so that it sustains without the need to constantly come back and tidy up – done right everything should have its place. This practice corresponds to a basic tenet of seamanship and the expression that is still in use “Shipshape and Bristol fashion.” The term dates to the early 19th century and is believed to be a reference to the practice of good seamanship at the port of Bristol where extreme tides were challenging for sailing ships moored alongside the quay. However, if everything was done right and all was in its place then all would be well, aka “Bristol Fashion.” So, two hundred years later today we continue to practice these same basic rules of seamanship to ensure safety and to be efficient. Keeping vigil over all these protocols means that we all must be ready to “Standby by our bunks” and be ready for inspection, we too can then be “Shipshape and Bristol Fashion.”